Retribution: Chapter 18

Life in Prison and the Trial

The chill of autumn came unexpectedly at the beginning of October after the unseasonably summery weather they had received that September. It was only then that people noticed the leaves changing color.

Paris seemed to have dozed off in the September heat and woken up to find herself several weeks later.

On a rainy October afternoon, Charles sat down in his living room with a tumbler of cognac and the newspaper. People were still talking about the arrest of Bruno Faucherie and there was talk of transportation to Cayenne. Charles had taken an interest in this story since he had been there when Faucherie was arrested.

When he was done with the newspaper, he picked up the copy of Les Miserables he was reading. He was at the part where Jean Valjean finds out about his daughter Cosette's love for Marius. Something about this scene touched him in a bittersweet way.

The clicking of heels could be heard on the the tiles in the foyer.

"Welcome home Madame," Lucille the maid said to Adèle, who was taking off her hat and raincoat.

"Thank you Lucille."

"Can I get anything for you?"

"A cup of hot chocolate would be lovely."

Lucille left to go to the kitchen and Adèle went into the living room. She came over and sat next to Charles.

"How was rehearsal?" he asked her.

"Exhausting," she answered, "I dropped by Charlotte's on the way back. The measles are going around and both of her girls have it. Good thing Charlotte and I both had it when we were little. Alexandre is staying with a friend until the danger has passed."

The photograph Charles was using as a bookmark caught Adéle's attention. It was of three well dressed young women standing on a perfectly manicured lawn. In the background was a modest sixteenth century chateau of white stone with round turrets with grey cone shaped roofs. In the corner was written the date 1911.

"I recognize that chateau, it's not far from where my parents live. It's called Chateau Aubrey. Did you know those women?"

"No, this is an old print from a fashion magazine that I found. You know how they sell old prints in those vendor's stalls by the river?"

"I like the girl on the right the best. The one in the center looks too haughty and the one on the left looks too insipid."

The three young women in the picture were all dressed in white frocks and sun hats. The girl on the right stood out because of her lighter hair; the other two were dark haired. She did not have the perfect features that the other two had but her wise, wistful eyes and kind, gentle smile were lovely and made her face radiate with prettiness.

Catharine was also spending a quiet evening at home, sipping hot chocolate and flipping through an album of old photographs.

The first photograph was of her as a seventeen-year-old debutante dated 1903. The next was an equestrian photo of her taken in 1911, when she was twenty-five. She would marry George Thomas later that year and her wedding picture came after the equestrian one.

Catharine thought about something she had overheard two women who were old friends of her's say at the party she had thrown the month before when they had thought she was out of earshot.

"Do you know who the blond girl in the blue dress is?" one of them asked the other, "That's Catharine's niece. Her mother was Catharine's sister, the one that died some years ago. Poor thing, she was always overshadowed by her sisters."

"Well, I don't think many women could have competed with Catharine in her prime." The other woman added.

"I never understood what men saw in her. She was always such a cold, awful woman."

Catharine had just shrugged her shoulders and ignored it. She had always known that there were few people who actually liked her.

Speaking of Madeleine, there was a picture of her at age nineteen dated 1909. It was almost uncanny how much Marianne looked like her at that age. Sometimes she felt that Madeleine's ghost was haunting her through her daughter.

Catharine compared the pictures of herself as a young woman to a photograph of Mathilde which hung on the wall. Mathilde took after her but there was not the uncanny resemblance between Marianne and her mother. Looking at Mathilde was like looking at an image of one's self done by a caricaturist. All of the faults Catharine had as a young woman were exaggerated in Mathilde. She had been stubborn and bossy and used to getting her own way. Many hapless suitors had earnestly devoted themselves to her in her youth and she had treated them all horribly and ended up marrying the worst of the lot. But Catharine had never been as nihilistic and focused on cheap thrills as Mathilde was.

The only good thing about her had always been her beauty and now that she was an old hag, she had little to offer the world. The years had humbled her somewhat and had also made her wiser.

Next to Madeleine was a picture of Mimi at age sixteen dressed in a blue evening dress. Mimi had arguably been the prettiest of the three of them and had been the petted baby of the family. She had been their good natured father's Claude's favorite while Catharine had been the favorite of their formidable mother, Emmeline. Not much had been left for poor Madeleine who had never quite fit in and it had been so easy to bully her.

On the next page was a photograph of the three sisters at a party celebrating Catharine's engagement to George Thomas. That night, Catharine had viciously mocked Madeleine to the point where she burst into tears. But that had also been the night when a dashing young man named James Beaumont had come into her life.

Madeleine's face looked back at Catharine from a distance of twenty-two years as if to say "I'm having the last laugh."

"A letter for you Lerou," a guard had said to Augustin.

Now he was sitting in a corner of his cell reading said letter. He did not recognize the handwriting on it but he recognized its scent. The paper had been sprayed with a perfume which smelt like lilies and honey; light and sweet and subtle.

"Who's the letter from, Augustin? Your maman?" a prisoner in a cell near his, a thin, pale young man with a gaunt face, called to him, "Little old Augustin misses his maman."

Augustin ignored him. He would never admit it but he was afraid of the other prisoners, anyone with any sense would be, but he sure as hell would never let them know.

"Dearest Augustin," his letter read, "I'm sorry I haven't been able visit you yet. Between shifts at the café and taking care of Manon, I haven't had much time for anything. Manon has the measles that are going around and since I had it when I was a child, I offered to take care of her. Also, I'm trying to limit my contact with people for fear I might spread the disease.

A few weeks ago, I went to visit your Tante Maude and Léon. Both of them are very worried about you miss you dreadfully. Léon is being brave and is a great comfort to your aunt; you would be very proud of him. He and your aunt are sweet people and I'm fond of them already. That was the twenty-ninth of September, Saint Michael's Day, and on my way home I made a wish at the St Michel fountain.

I never wanted to miss you but now I feel like I would visit you every day if I could. I don't know what to do, I can't bear being apart, and I can't imagine what it's like for you there.

The papers say that your friend Faucherie may get transported to Cayenne. I'm glad you aren't bad enough be sent there; I think I would die if you were that far away. Warmest Regards, Marianne."

Augustin folded up the letter and stashed it in his shirt.

That evening at dinner, the gaunt faced young man again teased him about his letter. When Augustin told him to mind his own goddamn business, some of his cronies held him while he pulled up Augustin's shirt to get at the letter, which he read aloud. Augustin spat in his face and was given a black eye.

At night, Augustin tried to stay awake as long as he could like a child who was afraid of having nightmares, but he was very tired. He had been able to get a hold of some paper and a pen and decided to write back to Marianne.

"Chérie," he wrote, "It's frightening and lonely here and when I read your sweet letter, it made me feel less afraid and alone. I can't bear having all these insane types around me all the time and I can't think straight. I'll write more tomorrow after I've gotten some sleep."

Marianne went to visit Manon after work some days later, bringing a pot of bouillabaisse which Madame Océane had made and a bottle of rosé. She found Manon sitting up in bed sewing when she arrived. Manon was over the worst of her illness but her luminous white skin but was still covered in blotchy red rashes.

"There you are, girl," Manon said when she saw Marianne coming through the door. Her soft voice was hoarse and she coughed.

"Madame Océane made you some bouillabaisse," Marianne told her.

"Tell her thank you."

Marianne put the pot on the stove to reheat the fish stew and opened up the bottle of wine.

"How is Anna?"

"Jean is hanging around again and she's still blind."

"Jésu, if he doesn't say something to that girl, I will."

A tray containing two bowls of bouillabaisse and two glasses of rosé was brought over to the bed and was placed on top of the quilt. Over supper, the two girls laughed about stupid things Mathilde and Agnés had said and done. Marianne told the story of Mathilde and some of her friends going to get their hair bobbed.

"Back at school, Mathilde would not shut up about it. She kept saying," Marianne switched to a perfect imitation of Mathilde's whiny soprano voice, "I think it looks very modern. I'm glad women no longer have to suffer the drudgery of being slaves to their hair."

Manon burst out laughing.

"It was ridiculous. Mathilde is about as bohemian as a bank. "It's you," I told her, 'I thought a bald monkey had gotten into your clothes.' 'You're a child, what do you know?' She said. I whispered under my breath 'Mademoiselle Capuchine' and she called me a witch. Tante Mimi was angry with me for what I'd said, but she's never said an unkind word about anyone her entire life."

When they finished with supper, Marianne gathered the bowls and glasses and went over to the sink to wash them. She went out to the water pump in the courtyard to fill a bucket of water for washing. While it was filling up, she took Augustin's letter out from the bodice of her dress and read it over yet again; she had read it countless times since it had arrived.

The bucket began to overflow and Marianne quickly had to turn it off.

"What's that you got there?" Manon asked her when she came back with the bucket of water, referring to her letter.

"A letter from Augustin."

The two girls shared a smile and a giggle. Manon and Anna were the only two people who knew about Augustin and Marianne was grateful to be able to talk to them.

Sitting back down on the bed, Marianne read the letter and Manon's usually placid face became serious.

"It's a terrible place, that prison," she said, "I wouldn't want to spend one night there let alone who knows how many years. People die in there all the time. They get sick or get beaten to death or the go mad and do the dirty work themselves. Not that I worry much for my brother Camille, as far I'm concerned the place is too good for him."

Johnny, who had been sleeping on the bed the entire time, curled up at his mistress's side as if sensing her distress.

"I better go wash those dishes."

Manon felt bad for worrying her friend but it had been necessary to warn her.

"Thanks for all you've done for me."

"You're my best friend, it's the least I could do."

Officer Desmarais came into Café La Premiere Étoile the next afternoon. He sat down at his usual table and ordered a cup of coffee.

"I'm going to Montparnasse after work," a pretty blond waitress said to the girl who was waiting Desmarais's table.

"What's in Montparnasse?" The other girl answered.

"La Santé Prison."

"You're going to visit Augustin?"

"I need to see him and know he's alright."

"I'm sure he is. Isn't his trial soon?"

"Yes, it's in a week."

"That's quick."

"Apparently, the powers that be want the criminals from the jewelry store robbery dealt with as soon as possible."

"That's good, you won't be waiting much longer to find out what's going to happen to him."

"I guess."

Desmarais got up from his table and went over to the tobacconist counter.

"Who is that girl?" He asked Madame Océane.

"Which one?" She answered.

"The fair one."

"Is she in any trouble?"

"No, I'm just curious."

"Her name is Marianne d'Aubrey. Pretty isn't she?"

"Yes."

"An orphan, poor thing. But she's got two rich aunts that live in St. Germaine. Good girl from a good family. Better than some of the little hussies I've had work for me."

"I heard her talking about someone named Augustin. Could he be Augustin Lerou, one of Faucherie's gang who was taken in for that jewelry store robbery?"

"I think so, I've heard her giggling about him with the other girls. He's made quite an impression on her."

"Is that so? Well, thanks for the information, Madame."

The impression Desmarais got was that Marianne d'Aubrey was a nice girl who had gotten mixed up with someone she should not have. Her loving aunts deserved to know that she'd been seduced by a dangerous criminal, so they could protect her.

Off of St. Michel was a narrow street lined on either side with dreary brick buildings with walls covered in many years worth of soot and grime and dirty and darkened windows. The pavement was full of potholes which filled up with rainwater to form black and muddy puddles which stank of garbage and always were there, even in the driest of weather. At its far end was an ugly, crumbling, three story building with a facade of decaying shutters of a rain faded black and grime clouded windows hung with rags.

Rooms there were cheap and some of them could be rented by night or by the hour, which made them very popular with girls like Marie and Cerise, who rented a corner of the garret. Most of the other attic rooms were used by an old gypsy woman who made a living telling fortunes and conducting seances.

Marie pushed back the frilly white curtains, the only clean thing in the room, to look out of the dirty garret window. It was almost evening and she would be back out on the streets again soon.

Over on the bed, Cerise was laying on her side with a yellowing pillow over her head, still groggy and irritable and wearing the dirty eyelet slip and torn silk stockings from the night before. Once in awhile she would moan in discomfort.

"What are you doing?" Cerise asked Marie.

"Looking out the window," Marie answered.

"Why?"

"I don't know."

Marie came and sat down on the stained mattress of the day bed across from Cerise's bed.

"You better get up, we should get ready for work."

Cerise gave an irritated moan.

"Suit yourself."

Marie pulled a small bag full of makeup and a mirror out from under the daybed. The reflection which looked back at her while she was doing her makeup was of a faded, buck toothed, creature and not the seductive girl she tried to imagine. She had never been pretty but night after night of boozing and tricks in alleyways had really taken their toll on her appearance.

Neither she nor Cerise could remember a time when they had not lived like this. Both of them had sprung up in the Paris slums like weeds through sidewalk cracks and had been letting their knickers down since age twelve. It had never occurred to either of them that life could be any other way.

It had rained for most of the day but the rain had stopped by evening. The rain soaked city let out a damp and stinking smell. Marie decided to ply her trade at the St. Michel metro station, where she was picked up by a man who paid her to suck his cock on board a metro car. He stood, holding onto one of the handrails, while she opened his trousers and began pleasuring him.

He came about two or three minutes later when they reached St. Sulpice.

Marie got off at St. Sulpice and loitered by a stairwell waiting for her next pick up. A devastatingly handsome young man with fiery eyes and smooth blond hair sticking out from his hat approached her.

"Good evening, Monsieur," she said to him.

"Excuse me, Mademoiselle," he said to her, his voice was a gravelly tenor, "Do you see that girl over there?"

He was referring to a blond haired girl in a yellow dress and greenish-brown sweater whom Marie did not recognize. She had thought she knew all the girls who picked up in this part of Paris.

"Bet she'd cost you more than a few sous. Frankly, I think it's past her bedtime."

The young man reached into the breast pocket of his shirt and took out some money.

"Here's money for the metro. I want you to follow her and find out where she's going. When you're done, come find me at the café across the street," He pinched her cheek, "And if you bring me the information I need, there's more where that came from."

The money he had given her was about as much as she made in a night and there was more to come. She did not see the harm in it, all she had to do was follow some hussy around and see where she was going.

Frankly, she did not see why he was interested in the blonde. She looked like a little goodie-goodie and could not possibly be going anywhere that interesting.

The girl got on the next train which she took to Montparnasse. Marie followed her to-of all places-La Santé Prison. She stopped and thought about who she knew that was in there and came up with Anton-le-Basque.

"You have five minutes, Mademoiselle," the guard said to her as she was brought into the cell block.

"Nice to see you, Marie," Anton greeted her, "to what do I owe this pleasure?"

"I thought you might be lonely." She answered.

"You're a sweetheart, you know that?"

They had not seen each other in few weeks and they spent a few minutes catching up.

The blonde was standing in front of a nearby cell talking to a wiry boy with curling dark hair. His large green eyes lit up to see her.

"I'm glad you came today, Chérie," he said.

"I needed to know how you were doing," the blonde to him, "You look so pale."

"I just haven't gotten much sun lately. This place ain't exactly San Tropez."

"If this place is San Tropez, they can keep it."

She stood up on her toes and leaned in through the bars to kiss him. He snaked his arms through the bars and around her waist.

"So that's what it looks like, love?" Marie said wistfully.

"Wouldn't know, never tried it," Anton responded.

"Do you know that type?"

"Yes, his name is Augustin Lerou."

"Time's up, Mademoiselle," the guard but in.

"Be careful tonight, Marie."

"Don't need to. I'm keeping my knickers on tonight, thank you very much."

Marie took the metro back to St. Sulpice and found the handsome young man at the cafe across the street.

"So," he prompted.

"She got off at Montparnasse and went to La Santé."

"Who did she go to see?"

"Some con they've got locked up there."

"Did you catch his name?"

"Yes, it was Augustin, Augustin Lerou."

The young man took some more money out of his pocket and gave it to her.

"Good girl."

After the tart had left, Edmond ordered himself another glass of crémant d'Alsace brut and lit another cigarette. The more he thought about it, the more the name Augustin Lerou seemed familiar to him. He must have heard it somewhere, in the papers, in relation to some jewelry store robbery everyone was talking about a month before.

So little Cinderella was fooling around with a convicted jewel thief.

Augustin was able to get a shower and a shave in that night which did him some good. As he was shaving in front of the mirror in the shower room, he saw the reflection of the gaunt faced young man, whose name he found out was Camille, pass by him, sneering.

At first, he had thought that Camille was just your average thug and that he could handle him but the more he saw of him and heard about him, the more he began to think that he was much worse than he had thought. It was said that he had set fire to his house when he was a kid and the fire had killed his entire family, aside from his little sister, whom the firemen were able to rescue. More disturbingly, it was said that he did unspeakable things to unfortunate fellow inmates he caught alone in the showers, just to show that he could.

The black eye Camille had given him was healing but was still fairly noticeable. He wondered if the dim light in the cell-block could have hidden it because Marianne had not said anything about it. The last thing he wanted was to upset her and get her worried.

Back in his cell, Augustin took out his pen and paper to write his letters. One was for Tante Maude and Léon, assuring them that he was alright and taking good care of himself. The other was for Marianne.

"Chérie," he wrote, "Remember that first time you came to see me, and I told you that you deserve to be able to walk into the Ritz wearing a nice dress and that you would be better off with one of those rich boys at your aunt's house? Well, I meant every word of it. Seeing you today, kissing you and holding you in my arms, made me remember how much I want you for myself, but I'm willing to let you go for your own good. I'm going to be here for who knows how long and it would do to have you waste your life as well.

Someday, I hope to read in the paper that you married a prince in Notre Dame, wearing a dress with a train as long as the Champs Élysées. But remember this: if you do meet a prince and he loves you with all his heart for the rest of his life, he still could never love you any more than I do."

On a brisk morning about a week later, a young American sat at his kitchen table, not thinking about anything in particular and drinking cup after cup of coffee and smoking cigarette after cigarette. When it was time to go to work, he bid goodbye to his wife and ten-year-old son and left his apartment on the Rue de la Montagne-Sainte-Geneviève.

At thirty-three, Aiden Murray was a stout but good looking man of Irish ancestry, being the first generation of his family born on American soil, with large blue eyes and hair that was a light reddish brown in the winter and a deep ruddy gold in the summer.

He had come over to France with the first wave of doughboys back in 1917. He had been barely seventeen at the time but could have passed for older. When the war ended, having fallen in love with a French girl and not seeing any reason to come home, he decided to stay in France, where he did pretty well for himself as a freelance journalist.

That day one of the newspapers that regularly employed him, was sending him to cover a trial. The story seemed straightforward to him: some young punk was going to be found guilty of a crime which he committed and was going to serve a jail sentence which he deserved.

The case was brought before the Court of Appeal at the Palais de Justice. A dark haired lad of twenty was brought out. He looked pale, thin, and sleep deprived. There was the faintest trace of a bruise over one of his eyes. But he stood there looking brave and stoic during the entire trial.

"Look how young he is," the crowd whispered about him. "He's got a face like a baby."

"You can still smell his mother's milk."

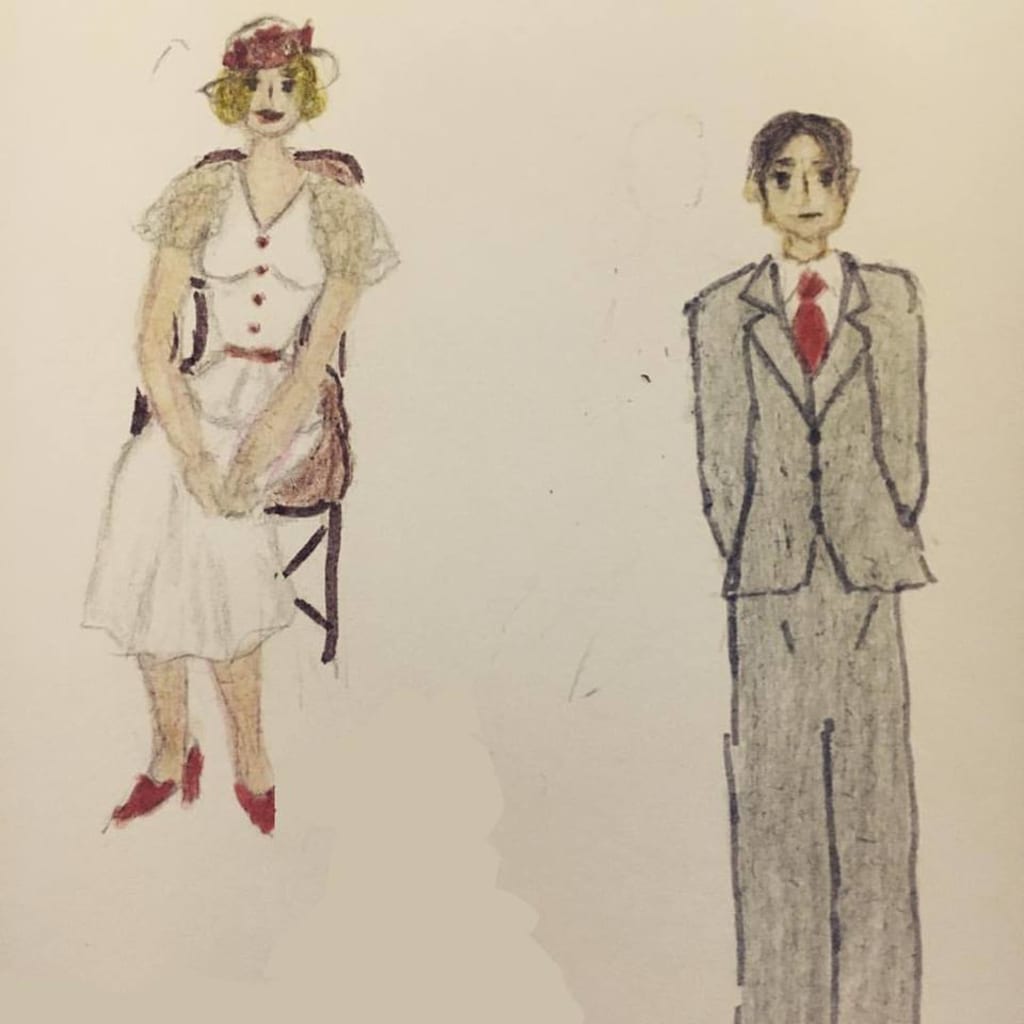

The trial moved swiftly and efficiently and Murray took notes throughout. The defendant's name was Augustin Lerou and he was twenty years old. He was born in Algiers and both his parents were dead. His parents had not been married, his mother being some Algerian slut his father had quickly abandoned. His Algerian nature had lead him into a life of crime at an early age and he had a history of pick pocketing and petty theft, the culmination of which being the theft of several items of clothing from a clothing store near the Pont Neuf called Bien Habillé which included a grey wool men's suit, a silk men's shirt, a red paisley tie, a grey hat, and a women's chiffon dress.

Seeing the young man's "talents" could be useful to him, Bruno Faucherie had sent his mistress, Hélène, to get him to enlist in his gang using her dark arts of... umm... persuasion. Being seduced by Hélène, Lerou agreed to be apart of the robbery of the jewelry store, L'Oie D'Or on the Boulevard St. Germain which resulted in the shooting and severe injury of its owner, M. Bijoutier. Several days later, Lerou and fellow gang member Anton-le-Basque were arrested at Le Monstre, a rowdy and disreputable dive off of the Latin Quarter.

Murray guessed that the popular mood was against Augustin Lerou and the defense did not stand a ghost of a chance. In a blink of an eye, the jury returned a verdict of "guilty" and the judge read the sentence.

"Augustin Lerou," the judge read, "You have been found guilty on one count of robbery and one count of accessory to robbery. You are sentenced to serve ten years for the first count and another five for the second count. That's a total of fifteen years."

With the pounding of the judge's gavel, fifteen years in the life of someone barely out of their teens were thrown away.

A woman sitting among the spectators got up out of her seat and ran towards Augustin as he was being taken away and had to be held back. She was a small, matronly lady with glasses and her mousy brown hair in a prim bun but it was as much as the guards could do to hold her back.

"My boy," she wept hysterically.

"I'm sorry Tante Maude," Augustin said.

A petite blond girl stepped forward to try to comfort the boy's aunt. She turned to Augustin and said, "I love you."

"I love you too, Chérie," he responded calmly.

"I think this sends out a strong message," said the chief prosecutor whom Murray had asked to give a statement "that in difficult times like these, no criminal behavior of any kind should be tolerated. Augustin Lerou will be in La Santé prison for the next fifteen years."

About the Creator

Rachel Lesch

New England Native; lover of traveling, history, fashion, and culture. Student at Salem State University and an aspiring historical fiction writer.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.